Margaret River

Everywhere we’ve been, people have said ‘you must go to Margaret River, it’s beautiful!’ so we thought we’d better go. Margaret River, it turns out, is both a town and the name of the region in Southern WA which is home to many beautiful places so, as usual, we had to pick just a few to visit as we passed through.

View from our free camp at Dardenup, WA on the way to Margaret River

Peppermint tree

The area had experienced an extraordinary wet spring so was very green and bursting with lush growth when we arrived in early November. As we drove, it felt strangely familiar; winding roads passed between small pastures and copses full of wild flowers. If the trees had been beech or oak rather than eucalyptus, this could have been Northern Europe. We liked it, the place felt like home and we could see why so many European people had chosen to make it their home. But niggling away was a feeling that maybe it was the other way around. I wondered if it looked like this because of the European settlers rather than being the reason they chose to make this their home.

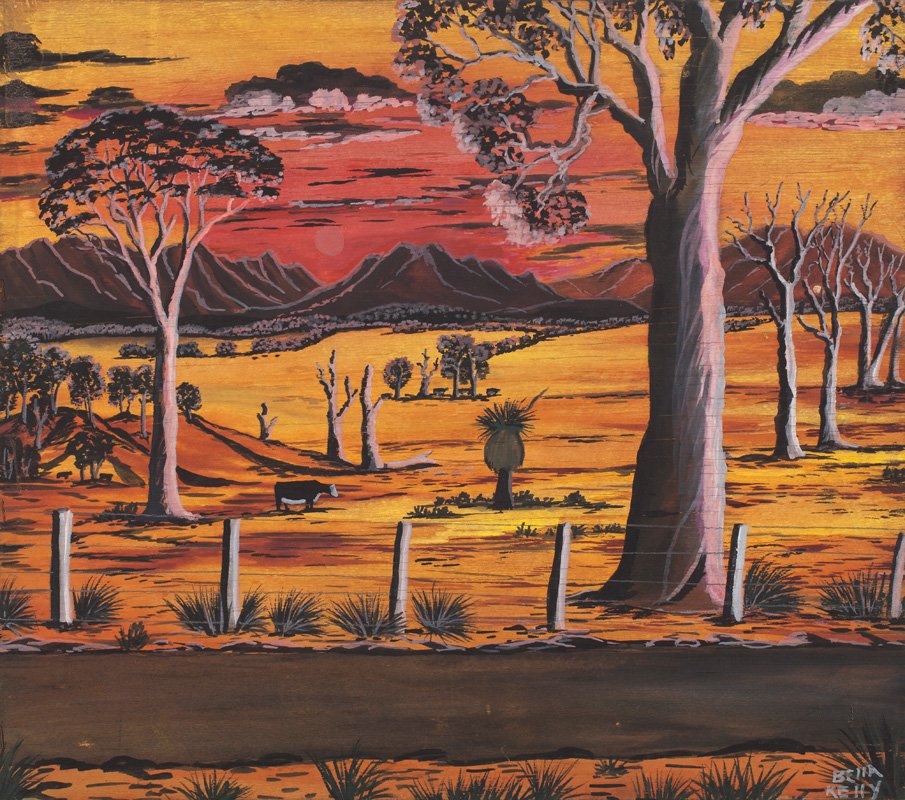

'Untitled (near the road)', a classic by Noongar artist, Bella Kelly, from the 1960s

We are on Noongar boodja (Noonga people’s country), specifically that of the Wardandi Pibelmen/Bibulmun language group whose ancestors and decedents are the traditional owners of the land on which the Shire of Augusta and Margaret River stands. Aboriginal people have inhabited this area for over 50,000 years and it is recognised by this Shire, and other organisations, that their land was never ceded but stolen from them. This recognition is recent and, although amendments have been made to state constitutions, unlike in Canada, USA and New Zealand Aboriginal people and Torres Strait islanders are still not recognised in the Australian constitution nor are there any treaties with them which, some feel, renders such recognition statements empty.

As in the rest of Australia, white settlement was the start of a devastating history for the Noongar people and the land they cared for. Their home would have been covered in eucalyptus, predominantly jarrah and marri forest, that was home to a vast number of endemic animal, birds and plant species. Some are still present, leading to the area being classified as a biodiversity hotspot, but many are now endangered or extinct. The Aboriginal people considered themselves to be part of the natural environment; there was reciprocity rather than dependence or exploitation.

White settlers did not share this reciprocity. They established the town of Augusta in 1830 and, shortly after, recognised the advantages of the extremely hard wood of the jarrah tree which was used to repair the HMS Success. Believing this would provide a business opportunity, convicts were deployed to clear the trees and cut them for timber. This proved so difficult that the convicts were recalled and logging didn’t get well under way until the 1870s when the WA government granted long term leases and ‘Special Timber Licences’ to stimulate the the timber industry.

Although initially friendly, relationships between the settlers and Aboriginal people deteriorated rapidly as the land was enclosed, forests destroyed and many indigenous people who stood in the way were slaughtered. In 1879, Ellensbrook Farm Home for Aborigines was established by the Church of England. This was one of many such establishments across Australia which were intended to turn indigenous people into ‘civilised, useful workers’. Aboriginal children were separated from their families and dressed in white folks clothing and ‘educated’ in an English manner; girls were ‘trained’ to be servants, men to be farm hands. All were forbidden from speaking their language, gathering together with their community or following any traditional activities. By the late 1800s, European disease epidemics such as influenza, venereal diseases and measles had further decimated the Aboriginal population. All this helped to achieve the government’s aim of pretty much extinguishing the language, culture and spirit of indigenous people

Between 1900-1914 approximately 17 million Jarrah railway sleepers were cut from the Margaret River area being transported as far as London for use in the cities Underground system; the remaining forest was considered not economically viable and the timber mills began to close. Now the land had been cleared, dairy farming was introduced which, along with domestic dogs and cats that predated unsuspecting indigenous creatures, prevented any hope of the native flora and fauna regenerating. Road and rail infrastructure connected the area to South Australia and in 1937, electricity was supplied but not on a 24 hour basis, and all this made it easier to exploit the land.

In the following decades up to the 1970s, salmon fishing, viticulture fruit and pine plantations became the main industries supporting considerable growth in the settled population with further decline and persecution of Aboriginal people. In the 1970s and 80s, tourism exploded as did all the industries needed to support both a permanent and seasonal influx of people. In the 1990s-2000s dairy farms, vineyards and timber plantations mostly moved from being family run to corporate-owned or state controlled.

Despite the recognition that jarrah-marri forests are important habitats, state controlled logging of virgin and regenerated forrest continues as does bauxite mining, both of which are considered more important than preventing extinction. Non-violent direct action by Nannas for Native Forest, among others, has prompted the WA government to propose an end to logging of virgin forest in 2024, the trade off is $350M compensation to the timber industry by way of soft wood plantations. Whilst some areas are protected and have successful rehabilitation projects underway, large-scale protection as a National Park is being prevented by pressure from industry; a familiar story across the globe.

Bussleton Jetty seen from the coastal path, WA

The area known as Margaret River is a bit of land that protrudes from the western coast of southern WA and, in the middle of the north facing coastline, is the small town of Busselton. Once a major port for the area, it boasts the second longest pier, or jetty as they’re called here, in the world after Southend in the U.K. Busselton jetty had been extended several times into deeper water to accommodate larger and larger ships until they became so large that the town was no longer viable as a port. The jetty continued to be used by locals until it was damaged by fire, probably set on the wooden deck by a chilly night-fisherman to keep warm, which apparently was a common occurrence. The federal government recommended the jetty be dismantled as it was no longer needed for international trade but the local community raised the funds to repair and upgrade it for the benefit of townsfolk and tourists.

Stretching 1.8km into crystal blue water of Geographe Bay, it now sports a little solar powered train which takes you to a fantastic Underwater Observatory at the far end. The north-facing coast captures the narrow, warm Leeuwin Current which flows down the west coast of Australia. This southerly current is responsible for introducing an incredibly diverse array of tropical and sub-tropical species into the bay, resulting in coral growth some 30 degrees further south than anywhere else in the world.

The Underwater Observatory is a tubular structure 9.5m in diameter and 10m tall with windows in the walls. It was constructed in Perth and floated down the coast before being sunk into a vertical position, emptied of water and fitted out as a visitor centre. This provides an excellent view of the fabulous warm water creatures that make their home on the wooden legs of the jetty and the fish who swim in amongst them. Watching the sea life, which you can do too on the live webcams, is mesmerising. The thick windows are a little distorting and reflective but the crochet coral made up for it!

Wiki-Camps came up trumps again and we camped at a one-pitch site in the garden of Swiss couple, Manfred and Marcel. This unusual spot amongst eucalyptus provided a quiet stay with use of the garden and indoor shower and loo. M&M were delightful to chat with, we learnt about their arrival in Australia over 40 years ago and how they designed and built their home. An evening visit from a roo in the neighbours garden was a lovely sight and the pagoda made a perfect early morning meditation spot. We had a brief stop in the small town of Margaret River in the middle of the shire, which is clearly quite a hip spot with a cosmopolitan feel to it. Amongst the leafy streets and trendy eateries there were hemp shops, eco cafés, barefooted surfboard makers and flashy cars; quite an eclectic mix.

Evening roo visit over the fence at M&M’s

Our site in M&M’s garden

The following night, we camped at a Fair Harvest permaculture garden run by two self confessed earth mother environmental activists who provide campers with spacious grassy pitches, composting loos and rainwater showers. Guests can explore the veg beds with their companion flowers and say hello to the chooks and ducks. We met a lovely young couple, Haiku and Nick, who significantly increased our confidence in using our camp oven to cook a wonderful Thai green curry over the fire pit whilst exchanging travel tails. It’s these places and experiences we really enjoy, way more than busy, well appointed caravan parks.

Fire pit at the permaculture garden

View from our caravan at the permaculture garden

Throughout the Margaret River area there are some of the most spectacular limestone caves in the world; there are so many there is even a cave trail along Caves Road which runs the length of the region. We love a ‘grotte’ and have visited many in England, France and South Africa but were completely blown away by the intricate decorations in the two we chose to visit in our limited time. Jewel Cave and Mammoth Cave where absolutely beautiful with well designed walkways and lighting which allowed excellent views of the largely undamaged structures and fossils of megafauna that once inhabited the area. In addition to stalactites and stalagmites, we learnt that the thin hollow structures hanging from the ceiling are called straws and if the water flows out the sides, a helictite forms.

Mammoth Cave, Margaret River, WA

Emerging from a sink hole and walking through the fragrant flowers in the lush karri forest surrounding the Jewel cave was a delightful contrast to the cool damp cave. We saw many tiny orchids nestling like jewels amongst the grasses and the whole area was humming with life. The heady scent of the bush is quite the most magical experience; it felt as if the very trees and flowers were permeating through my body and lifting my spirit., carrying me along on the breeze.

The way out from Mammoth Cave via a sink hole

Walk through the karri forest after the darkness of Mammoth Cave

Australia is a place of many contrasts; desert to rain forest, vast open space to sprawling cities and lush forest to charred stumps. In the weeks after we left Margaret River, temperatures soared to over 40C for three weeks turning the lush spring growth to crispy dry tinder. Sparked by lightning, bush fires devastated the Caves Road area destroying over 6000 hectares of pristine bush. If that’s hard to envisage, one hectare is about the size of a 400m running track and 6000 is an area equivalent to the entire city of Cambridge U.K. and several of the surrounding villages.

Image from ABC News

In Australia, bush fires are not new but the increasing frequency of prolonged extreme temperatures and lightning storms are producing the ideal conditions for some of the most ferocious fires to proliferate. There is now no doubt that this being driven by climate change as a result of human activity, in particular the burning of fossil fuels. While the bush was burning, the Australian government continues to support the opening of new coal mines and oil fields. I cannot comprehend this at all. The distress I felt at the news of the fires burning the forest and all that lived there, right where we had breathed the scent of the bush flowers on Caves Road just weeks earlier, was was unbearable which made finishing this episode so difficult.

Image from ABC News

Our next steps take us to more ancient forest which, for now, remains intact.