Victorian High Country

This is the second in a short series of blog posts that share our experiences while pausing in Victoria where we based ourselves at my brother and sister-in-law, Ken and Roberta’s home in Melbourne. These are grouped by the type of activity rather than being in chronological order. The previous one covered family, friends and activities in Melbourne and this one brings our experiences of travelling with Ken and Roberta. I’ll cover the Troopy conversion process and a few more Victorian experiences a bit later.

The Great Dividing Range of mountains runs roughly parallel to the east coast of Australia and stretches from beyond the northern most tip of Cape York right through Queensland, New South Wales and into Victoria where is turns West and fills most of the eastern portion of the state. Officially named the Victorian Alps but commonly known as The High Country, these mountains are now part of the Alpine National Park and include the origin of most of Victoria’s waterways. It’s not an especially high range with the highest peak of Mt Kosciuszko 2,228m (7,310ft), a little more than half the hight of Mt Blanc in the French Alps 4,804 meters (15,774 ft), but high enough to provide a variety of habitats.

The National Park status has helped to protect the area from commercial mining and logging but there remains an on-going battle between big business cashing in on exploitation of natural ‘resources’ and those seeking to preserve this unique environment. There has been much coverage of widespread and systemic illegal logging by the state-owned VicForests which has been found to have destroyed the habitats of protected species, logged slopes steeper than 30 degrees and massive areas of land they do not own. The regulator appears to be doing little to prevent this destruction and sanctions are of no consequence in comparison with the profit to be made so many wonder who is regulating whom.

Denuded slopes and plantations where once there were native trees

Even with all this going on, there is still a vast expanse of forest which is home to great beauty and diversity. Victoria has some interesting country towns and areas steeped in history of the early European settlers. There are many free campgrounds and well cared for tracks, as well as some pretty rough ones, that provide access to amazing views and long abandoned historical sites. Unlike many four wheel drivers, we are not really interested in undertaking a tricky off-road drive just for the challenge of the track. I do appreciate the concept though, for many years we’ve sought out great motorcycling roads and gone up and down them because ‘it’s all about the road’. Today, I feel that the road, or indeed the track, and the vehicle needed to travel it, is purely about access. I continue to feel uncomfortable burning fossil fuels to indulge my desire to see stuff and acknowledge that, in the absence of an alternative to reach these places, the best I can do is take the shortest route and minimise both the overall fuel consumption and the impact on the track.

With this in mind, when we were invited to join a family gathering north of Ballarat, we combined it with a trip in the nearby Creswick Regional Park. This land was stolen from the traditional owners, the Dja Dja Wurrung people who have a wonderful dreamtime story about two feuding volcanos which explains the land formations. They inhabited this country long before colonial settlers chose to dig for gold, cut down virgin forest and destroy indigenous communities and it’s important that these stories are shared and not lost.

In 2013 the Government of Victoria and the Dja Dja Wurrung people entered into an agreement recognising the traditional owners of their country and acknowledging the history of disbursement and dispossession that has affected them. Of course this did not return their land because the decedents of the invaders now officially ‘own’ the land, so the traditional owners now officially ‘own’ just 2.8% of what was theirs. I can see the difficulty because the decedents weren’t the original thieves so why should they give up the land they have cared for for generations. Such damage can never be undone, that’s why it's important to prevent such atrocities happening in the first place.

Twin Kimberley Karavans at Slaty Creek Free Camp near Creswick, Victoria

We set up camp with Ken and Roberta camped at Slaty Creek campground, a great spot among the gum trees at the edge of a creek. As there was no fire ban in place, we enjoyed evening campfires and Ian learnt up close about the volatile properties of eucalyptus leaves as a natural fire lighter. Ken and I quickly moved back as he added a fallen but leafy branch to a stuttering flame just in time to see the ball of oily flame whoosh up, but it certainly got the fire going!

We visited the historic town of Clunes, the site of the first gold strike in Victoria which was a trigger for the gold rush in the 1850s. The original town main street is very well preserved and has provided the backdrop to many films including Mad Max and Ned Kelly. It is now home to the famous Clunes Booktown Festival which attracts 15-20,000 people every year and helps support more bookshops than would normally survive in such a small place.

Henry and Maggie Condie, Wonthaggi Cemetary, Victoria

A second trip, also with Ken and Roberta, took us first to where my ancestors on my father’s side of the family settled on their arrival in Australia, the town of Wonthaggi, on the south coast. My great grandfather, Henry Condie and his wife Maggie emigrated from Scotland after adopting their nephew, Hugh Crawford, when his own parents and siblings died in the great influenza epidemic. Henry was a mine manager and, although he survived a terrible accident down his mine when many men lost their lives, Maggie vowed that their son would not be a miner. Hugh wasn’t told of his adoption until he was about to marry so he chose to combine his birth and adoptive names and so the family name became Crawford-Condie. Hugh and his wife Georgina, went on to have two sons, Ken, who died during WWII, Ian (my father) and a daughter, Ailsa. I’m not really one for visiting graves; my father’s ashes were scattered in the woods at Whiteleaf and mum’s grave is in a woodland burial ground near Beaconsfield and, although I love the surroundings, I’ve never felt that either of them are in these places in person. However, I was surprisingly moved on finding Henry and Margaret’s final resting place in old part of Wonthaggi cemetery, perhaps because I imagined Hugh choosing the inscription on their shared headstone and maybe also the knowledge that it is possible no one will visit again.

Our trip turned northwards and headed for Minniehaha Falls at Hiawatha (yes really!) up in the High Country. We set up at a free camp within the sound of these pretty falls were we could again sit around the camp fire in the evenings.

Our Troopy next to Minnehaha Falls, Victoria

Our campsite with Ken and Roberta at Minehaha falls

On a beautiful hot sunny day we experienced one of the highlights of our trip so far, the Tarra-Bulga National Park. We walked down into the rainforest, deep in the gully amongst some of the most beautiful plants and trees I’ve ever seen. Parks Victoria work in equal partnership with the Gunaikurnai people, the traditional owners of the land, to care for this most precious place. This short film of a park ranger explaining the area is a really lovely introduction and well worth a watch. At the time we visited, I was really struggling with a poorly functioning and very painful hip and my determination to complete the steep uneven walk probably did more harm to it but the experience filled my spirit with such joy it was worth every step. Below are a few pictures that provide a hint of the exceptional beauty of the rainforest gorge, the suspension bridge and the magnificent trees.

In the middle of this trip, Ian and I had a day out to the town of Metung on the banks of the tidal Gippsland Lakes. We walked along the boardwark and later learned of a Gunaikurnai dreamtime story about a prominent lakeside rock. The legend goes that some fishermen made a good catch and ate the fish around their campfire. The fishermen, however, did not share their catch with their dogs, despite having more than enough to eat. As a punishment, the women, who were guardians of social law, turned the greedy men to stoneThis was to meet the father of a potential buyer for the white troopy we bought when we first arrived. He was viewing it for his son in Perth and, if it was as described, he had agreed to drive it over there. Thankfully, he was impressed and shared his thoughts with his son and the deal was sealed a few days later. With this secured, we were all set to buy our brand new troopy we had ordered eight months earlier that had arrived at the dealer four months late due to the international shortage of semi-conductors caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The boardwalk at Metung, Victoria

Legend Rock, Metung (photo from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metung)

Note the fallen tree as the track turns the corner!

Ian and I travelled home separately from Ken and Roberta to attend an appointment in the city and we chose to take what appeared to be the most direct route out of the forest. In doing so we learned a further lesson; not to rely on electronic maps to negotiate off road tracks. Much of what looks like a real roads may well not have been travelled for some while and no one is checking for obstructions and reporting on Google or Garmin maps. Hence the need to reverse our caravan along a narrow overgrown muddy and branch-strewn track and do a 99 point turn after meeting a fallen tree that had clearly been there for months. It reminded me of a friend who went into a country fuel station to seek help because his GPS had packed up, the old boy behind the counter advised in a slow drawl with a grin on his face “G.P.S? What you want boy is an M.A.P.” We now have both paper and electronic means of mapping!

At the beginning of January, in the week we had no vehicle, we took the train to northern Victoria to the town of Benalla. We were met by my cousin Tric, the youngest daughter of my mum’s youngest sister, Helen, and the closest in age to me of all my cousins. We stayed on Tric and her husband, Dion’s, small farm out in the bush and caught up on memories of when we first met in 1976. We hadn’t kept in touch so there was lots to fill in and learn about each other. On a really wet day, we visited the historic site of Stringybark Creek where a shootout between police and Ned Kelly’s gang resulted in the death of three police officers and the gang being outlawed. The story of the Kelly gang is deeply ingrained in Australian Colonial folk lore but there’s way more to it than horse rustling and thievery. Were the Kelly gang hunted down because they chose to become outlaws or did they become outlaws because they were oppressed Catholic Irish immigrants in a predominantly Presbyterian community? Descendants of both the Kellys and the police officers still live in the area and provide very different perspectives on the story as part of the display at the site. It’s a fascinating example of how the lives of poor people are shaped by wealthy colonial forces assisted by police collusion. This is still happening all over the world and history is written by the latter to suit the storyline from their perspective.

After Christmas and equipped with our new, but yet to be fitted out, troopy we undertook our third trip to the High Country with Ken and Roberta and the last in our Kimberly Karavan. We headed for the small town of Dargo and set up in a free camp along a dirt track about 10km north of the town called Ollie’s Jump Up. The campground initially looked unpromising in the gloomy weather close to sunset but was transformed the next day in the sunshine. It was in the loop of the lazy Dargo river and had a great swimming hole where the water swirls around the bend; a great spot to cool off at the end of a hot dusty day.

Twin Kimberlys at Ollie’s Jump Up, Dargo, Victoria

Our rig in the distance, Ollie’s Jump Up camp ground

Swimming hole at Ollie’s Jump Up

The traditional owners of this land are the Brabralung people, one of the five clans making up the Gunaikurnai people inhabiting Gippsland, which stretches from the southern slopes of the Alps down to the southeastern coast of Victoria. These clans, who thrived for thousands of years in the area, met up in the high country to feast on the Bogon moth, share stories and participate in ceremonies. This way of life came to an abrupt end when colonial settlers arrived. After allowing the indigenous people to show them the tracks through the challenging terrain and where to find water, they forced them from their country and most were killed, enslaved or sent to missions.

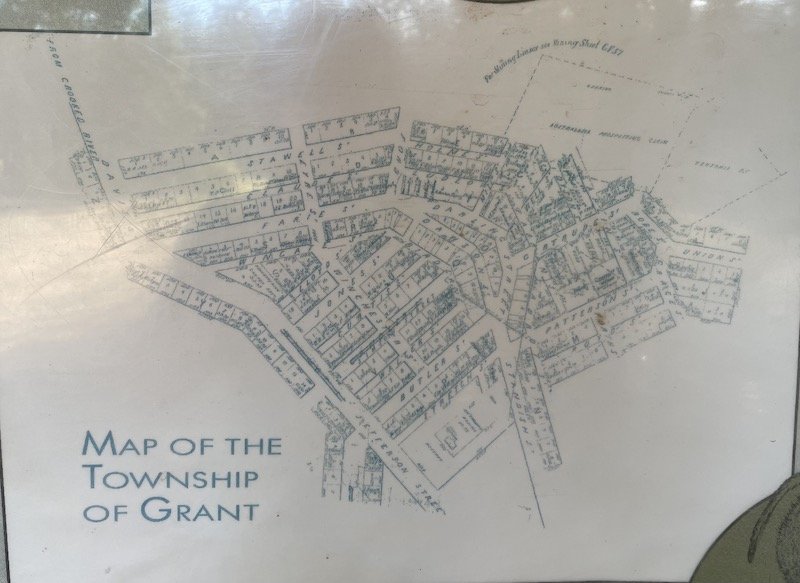

Dargo was established as a town to service the gold fields and, unlike many others, survived beyond the short lived gold rush. It seems this was because it was on the route linking Omeo and Harrietville and surrounded by broad river flats suitable for agriculture, so it wasn’t dependent upon the mine works. Other settlements in the area were established, populated with hundreds of people only to be deserted within a few years. One of the most notable is the town of Grant established up on a high ridge when gold was first found in 1862 and by 1865 it had over a 2000 residents, 15 hotels, a courthouse, church, school and numerous shops. But only the following year, the gold had all but dried up from 3,868oz in 1865 down to 154oz in 1866 and the population rapidly declined to just two families by 1902. The last family only managed to continue running the post office because they posted letters to themselves! When we visited, there was nothing left of the town except a few grave stones in a formal church yard amongst the trees. These were being maintained by a local historical society.

We visited the remains of Grant on the way to an amazing lookout where a trig point is situated at the end of a challenging drive along the Blue Rag Ridge Track. After rising over several interconnected ridges, it follows a razor back just wide enough for a single vehicle with a steep drop to each side and made of a combination of dirt and rocks of varying sizes, many of which are loose. We’d heard that the most popular time to traverse this track was early morning so we chose to go up in the afternoon as the last thing we wanted was traffic. I drove up and had to pause several times on an uncomfortable tilt for earlier visitors to pass. Everyone stops for a brief word of thanks or to provide advice on a tricky section of track and sometimes to share a joke about breathing in to get past each other; a way of acknowledging mutual fear. It reminded me of the exchange between motorcyclists after a scary moment when we would describe the buttock-clenching fear as ‘sucking the stuffing out of the seat!

Blue Rag Ridge Track, High Country, Victoria

There were multiple double takes when vehicles drew alongside to pass as I was the only woman driving. I’m not sure if they were aimed at me or Ian in the passenger seat, but it was a little surprising not to see more women driving. Ian and I have had similar driving experience over the years and we learnt about off roading together on arrival in Australia, so we haven’t thought twice about sharing both the dull and the more challenging drives. On our travels, we’ve met a few couples who have taken days in turn or shared a very long drive, but mostly it’s the men driving and women only do so if they have to. I’m not sure if this is the result of real or perceived confidence issues by the men, women or both.

At the top we put the awning out and all four of us sat in shade having a cup of tea admiring the truly breathtaking view. From a height of 1700m, the area we surveyed was vast with no obvious signs of habitation as far as we could see. There had been bush fires in the area some years ago so ferocious that the the trees were burnt beyond the point of recovery and some hillsides were covered with long dead Snow Gums bleached white by the sun. It looked like a ghost forest and there was evidence of the type of soil erosion that sets in when tree roots cease to hold the hillside together. Beautiful alpine flowers had taken advantage of the lack of canopy cover and the grassy areas were filled with short stemmed blooms of very colour.

Our Troopy next to the trig point at the top of the Blue Rag Ridge track, High Country, Victoria

Wild flowers about half way up the Blue Rag ridge Track

Wild flowers carpeting the slopes alongside the Blue Rag Ridge Track

The last place we visited on this trip was another abandoned gold mining settlement called Talbotville. As the most direct route was impassable through rain and deep river crossings, we accessed along another narrow dirt track, this time hugging the steep hillside, which eventually opens out to a large grassy flat where the town once stood in a loop of the Crooked River. It is now a lovely free camp ground with space for maybe 100 rigs and, on the sunny day we visited, it was filled with the sound of kids playing it the water.

Ken had recently had a new snorkel fitted to his car and one of the reasons for this visit was that the surrounding tracks criss cross the river providing an opportunity to test it out. Having never crossed more than a deep puddle, this was a first for us and we’d prepared by watching YouTube videos to learn the best techniques and then followed Ken to see what happened to him first! I drove through ten river crossings then swapped so Ian could do them back. We filmed each other and Ken so we could analyse our performance, yep, sad but true. We took this as a practice run for our trip to the top end when often the only alternative to crossing a river is to turn back. By the time we do that, we’ll be living full time in our new troopy so our aim is not to sink it in a poorly judged river crossing.

Here’s a short video of me doing one of the longer crossings.

Join us next time to hear about our Troopy fit out.